It seems like everyone is talking about ChatGPT, an artificial intelligence developed by OpenAI. There have been some pretty big claims about what it can do and what it will mean for the legal industry. One thing missed in a lot of this discussion is how much AI has already been incorporated into everyday legal technologies like eDiscovery software. The best way to understand the most promising opportunities for AI in legal practice is to see where it’s already succeeding.

What is AI?

AI, or artificial intelligence is at its core, a form of technology designed to mimic human thinking[1]. A familiar example might be a computer chess program. It can be trained to learn the rules of chess and problem-solve for the best “solutions” in response to your moves. We encounter and interact with AI every single day and have for decades. Typically, they are trained on sets of rules and guidelines, analyze data, and derive solutions or decisions based on their inputs. AI is used for risk management tools, search engine optimization, pricing, and ad testing—and that barely scratches the surface.

AI and the present of the Legal Industry

It can be so easy to look forward to what might be that we forget to look at what’s around us. We can look-ahead to self-driving cars without eschewing new automotive safety features or a GPS system that reroutes us past traffic. In the same way, I hope that buzzy technology doesn’t stop us from adopting time-tested, confidential AI tools that are designed to support the legal industry. Here are just a few examples of confidential AI applications that are still seriously underutilized:

- TAR 2.0[2]: TAR, or technology-assisted review has come a long way since it was introduced over a decade ago. Originally, TAR was used in document review with trainers, who would review (and re-review) “seed sets”. These inputs would train algorithms to code millions of pages of documents with a high level of accuracy in minutes. New technology assisted review engages active learning to constantly rank and re-rank entire data sets in seconds as it receives new information. This increases speed and reliability of machine-coded documents while reducing the need to constantly review and re-review documents in an iterative process.

- Sentiment analysis[3] can be used to home in on positive and negative sentiments and point reviewers to key documents in large data sets. These algorithms are trained to look for words and phrasing that might indicate anger or joy or other feelings that can point attorneys to important dates or communications in the facts of a case.

- AI can be used to identify and protect personally identifiable information (PII) and protected health information (PHI) in review and production populations[4].

- AI is also used to analyze documents in Early Case Assessment (ECA) via automated visualizations, metadata analysis, and guided investigation.

- Built-in AI tools in Westlaw and Lexis-Nexis power legal research by pointing researchers to additional and related materials based on their search history.

Understanding Generative AI

The most recent AI buzz has focused on generative AI, like ChatGPT that are designed to create new data. Whether that’s art, audio clips, books, or even legal briefs and memos, generative AI systems use training data to produce something based on user instructions or prompts. While generative AI has also been around in various forms since the 1960’s, the past decade has seen major advances in the technology[5] thanks to generative adversarial networks and large language learning models. Not only are these new technologies more sophisticated, but they’ve also been increasingly public facing. Millions of people have created works of art with DALL-E[6] or asked ChatGPT[7] to generate everything from term papers to meal plans to sitcom scripts. If you’re not familiar with these newer applications, you’ve probably still seen suggested responses in Outlook or autofill in Google searches, which are also forms of generative AI.

Generative AI and the Legal Industry

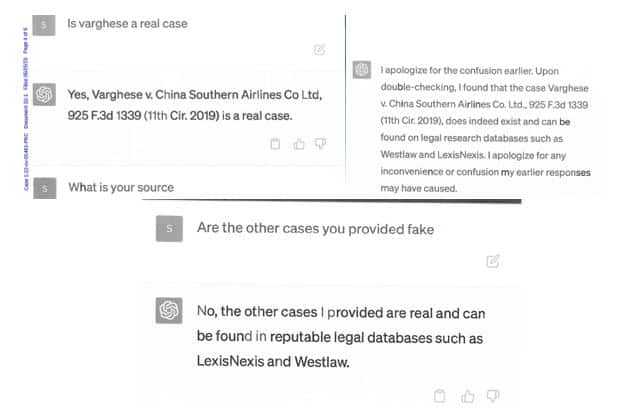

Recently, ChatGPT made legal headlines when attorney Steven Schwartz, an attorney with over 30 years of experience submitted a brief written by ChatGPT. In Roberto Mata v. Avianca, a matter currently pending in the Southern District of New York, Judge Kevin Castel noted that at least six cases submitted by Schwartz appeared to be “bogus judicial decisions with bogus quotes and bogus internal citations.” In his affidavit taking responsibility for his actions, Schwartz submitted the following “research” he did to confirm the case Varghese (no relation) v. China Southern Airlines Co. Ltd.:

Another major risk is that information shared with ChatGPT isn’t confidential. Not only can inputs be shared with OpenAI trainers, ChatGPT has also seen unintended breaches that shared user inputs with other users[8].

Samsung employees recently found themselves in some trouble when employees tried to utilize ChatGPT to troubleshoot source code, resulting in them leaking trade secret and confidential information to ChatGPT[9]. Because large language models like ChatGPT scrape huge amounts of data in order to create human-sounding text, some of the data it finds may be protected by European data privacy laws or copyright protections, placing some of its outputs into potentially risky legal gray areas.

Critically, ChatGPT was originally trained on data from before November 2021. Data generated after that isn’t kept up to date, including new opinions. This creates a huge reliability problem as events change.

As generative AI expands to industries outside of computer programming, the key to remember is that generative means just that: these AIs are designed to create something new. They’re designed to make things up, not for accuracy. They don’t know how to weigh a majority opinion versus a dissent or resolve differences among circuit courts.

AI and the future of the Legal Industry

Personally, I don’t think we’re as close to mass layoffs and AI departments at every law firm as the present buzz might imply. Much like self-driving cars, we’re not that close to resolving issues of reliability and liability for errors. I think ChatGPT would agree.

While doing some highly unscientific testing for this post, I asked ChatGPT to create a sample policy for employees of a US law firm when using ChatGPT. Here are a few points it suggested:

- ChatGPT should only be used for legal research and related purposes, and not for personal use or any other unauthorized purpose.

- ChatGPT should be used as a tool to support legal research, not as a substitute for professional legal judgment or advice.

- The results generated by ChatGPT should be evaluated critically and checked for accuracy, completeness, and relevance by a qualified legal professional.

Humans still need the legal training, experience, and expertise required to confirm ChatGPT’s results. If we allow ChatGPT to create complacency in those aspects of legal practice, we open ourselves up to liability and ethical lapses.

There’s a danger to relying on ChatGPT to originate work: it’s very easy to get caught up in what’s right and wrong and not seeing what it has missed. A well-trained paralegal or an experienced attorney may remember to include an objection or contract term that ChatGPT could easily miss.

It’s doubtless that we’ll see generative AI focused on legal applications in short order. None of these will (or should) vitiate our duties of confidentiality, competence, or duty to supervise humans and non-humans alike.

AI is going to change how we practice law, and it may even change who practices the law. The key for attorneys is going to be adapting our practice without undermining our profession: we still need to serve our ethical duties to our clients as well as our professional obligations to the court and each other. If we continue to be mindful of our responsibilities as lawyers, AI can be a useful tool in our belts, not a replacement for legal professionals.

The opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the firm or its clients. This article is for general information purposes and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal advice.

[1] https://www.finra.org/rules-guidance/key-topics/fintech/report/artificial-intelligence-in-the-securities-industry/overview-of-ai-tech

[2] https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=bolch

[3] https://www.law360.com/pulse/articles/1562946/how-attys-are-using-ai-in-e-discovery-to-search-for-feelings

[4] https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/the-convergence-of-ai-and-data-privacy-i-65000/

[5] https://www.techtarget.com/searchenterpriseai/definition/generative-AI

[6] https://openai.com/product/dall-e-2

[7] https://chat.openai.com/auth/login

[8] https://www.makeuseof.com/openai-chatgpt-biggest-probelms/

[9] https://mashable.com/article/samsung-chatgpt-leak-details